Adolescent Suicide Nonsense in National Academies Report

Today's publication by National Academies contains an egregiously wrong suicide trends graph misused to undermine the gravity of the recent suicide rise among children and adolescents.

Today the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released a report titled Social Media and Adolescent Health authored by a Committee on the Impact of Social Media on Adolescent Health consisting of eleven scholars.

Unfortunately, the authors included an egregiously erroneous graph of adolescent suicide trends that plays a crucial role in their dismissal of high suicide rates among teens.

Note this is part of a series of article on the National Academies report:

National Academies Misinformation Undermines Concerns about Adolescent Mental Health

Illusory Balance: How National Academies Trivialize Serious Risks Associated with Social Media

Erroneous Figure

The erroneous graph is Figure 1-4 (page 20) early in the report:

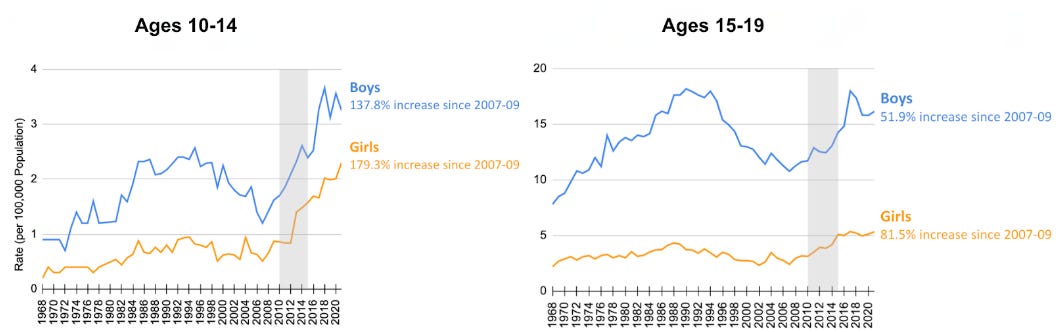

The graph shows current suicide rates for boys as being far lower than they were circa 1990 — which is completely wrong. In reality, the proper graph for ages 15-19 boys suicide trend is below (at right):

Graph prepared by Zach Rausch (see his excellent article Suicide Rates Are up for Gen Z Across the Anglosphere, Especially for Girls)

As we can see, suicide rates for teen boys were as high circa 2018 as they were at their previous peak circa 1990. Furthermore, the recent rates are much higher than they were ever before for early teens (ages 10-14).

The problem with the inclusion of the erroneous graph goes beyond the public misinformation that it spreads, given its prominent placement in this important report — another major problem is that the authors outright rely on the graph to make severely misleading arguments, as we shall see below.

Crisis? What Crisis?

The first problem is that the authors misuse Figure 1-4 to imply there is no urgency regarding the high suicide rates among adolescents, writing that “confusion extends even to assessments of whether youth mental health is in a state of crisis” (page 19) and then referring to Figure 1-4 where recent rates are incorrectly shown as being far below those circa 1990. The authors then go so far as to call the recent rise an “apparent” spike (page 19) — as if there was somehow reason to doubt it is even real.

The authors further imply there is nothing special about the recent adolescent suicide wave by writing that “suicide mortality has increased in almost all groups over the last twenty years, this is not problem unique to adolescents” (page 19) — while completely omitting the inconvenient fact that the increases are far higher for children and adolescents than for adults, including teen adults, as I’ve shown several years ago in The Rise and Adult Suicide:

The Committee on the Impact of Social Media on Adolescent Health should not be relying on withholding crucial information in order to argue there is nothing unique about the rapid rise in adolescent suicide.

Nonsense and ‘Cyclicality’

The second problem is that the authors misuse Figure 1-4 to make a fatally flawed argument that the recent rise is merely the result of ‘cyclicality’ in adolescent suicide (page 19):

Data on suicide, the most extreme consequence of psychological pain, indicate that the apparent spike in problems over the last 15 years may be more an example of long-term cyclicality, following a relative low point in the 1990s and 2000s (see Figure 1-4) (Levitz, 2023; Rinehart and Barkley, 2023).

A graph showing two peaks is not a credible indication of ‘cyclicality’ — at least not in science. It is astonishing the authors did not first check if there were adolescent suicide wave peaks circa 1950 and 1920 before advocating a cyclical nature of adolescent suicide trends.

The authors wade deeper into nonsense by warning that “an overemphasis on the recent past could lead an observer to a mistaken emphasis on recent explanations” (page 19) when in reality any causes of recent increases must themselves be recent, even if the chain of causation goes further back in time. That is unless ‘cyclicality’ is some kind of a supernatural phenomenon exempt from ordinary cause and effect laws of science.

Discussion

It is alarming that all of the eleven (11!) experts on the health of adolescents failed to immediately note that Figure 1-4 is egregiously wrong — should such experts not have obtained at least an elementary understanding by now of the most important (suicide!) health trends among adolescents?

It is also frustrating that these experts based much of their key arguments on a graph they took from a blog (which was long before publicly reported to be wrong1) instead of basing it on data obtained directly from CDC (which would have taken them 10 minutes top).

Note: my criticism of the National Academies report is not intended to defend, not to mention promote, the social media culprit theory.2

Conclusion

We need serious and impartial scholarship when dealing with such a grave topic as the recent rise in adolescent suicide, and the graph fiasco in the National Academies report is not a good sign that such a scholarship has been undertaken by the Committee on the Impact of Social Media on Adolescent Health.

I first alerted Rinehart and Barkley back in March, shortly after they posted their article:

The single like is actually from Barkley.

I also repeatedly warned Rinehart and Barkley about the error in the comments section under their Substack article, including a reminder a couple of months ago:

Despite these warnings, the authors never fixed the graph (as of Dec 13) and it keeps being referred to in various articles (such as Levitz in NY Mag) and now even in the National Academies report.

I’ve spent much of my time critiquing the notion of social media being the primary culprit behind the mental health crisis of adolescents (see numerous articles in The Shores of Academia), and I am in particular skeptical about the suicide rise being explained primarily by social media and smartphones (see The Trouble with Suicide). I even proposed a de facto rival theory of the suicide rise (see Childhood Trauma and Youth Suicide Rates).

That said, the idea that youth suicide can be cyclical is not all that farfetched though. Strauss and Howe would likely agree that there is a four generation cycle to virtually all social phenomena. See "The Fourth Turning". Additionally, as renowned sociologist (and youth rights activist) Mike Males has noted before, youth suicides had not that long ago (i.e. 1960s and earlier) often been mislabeled as "accidental" deaths to avoid the stigma that was stronger back then. One good way to test this theory is to look at suicide rates in Japan, a country where there is practically no stigma associated with suicide, and never really was (heck, they even have a forest dedicated to it at the foot of Mount Fuji). And they made a lot of progress reducing their historically high suicide rates, that is until the pandemic hit and their progress began to reverse.