Youth Suicide Rise

The doubling of adolescent suicide 2007-17 will be the primary subject of my new Substack series in which I will update my original series from 2019 with new data and a wider scope of inquiry.

The Rise

Between 2007 and 2017 the number of suicide deaths among U.S. adolescents aged 12 to 17 more than doubled from 805 to 1,719 even though the population of that age group decreased by nearly a million:

The rates remained high after their peak in 2018, roughly double the 2007 rate (provisional CDC counts for 2023 indicate a 6.2 suicide rate).1

The relative increases have been steeper for girls and young adolescents, so much so that age 10-14 suicide rate tripled and outright quadrupled for girls in that age group.

Child suicide (age below 12) also doubled, though it remains rare.

Adult suicide has increased as well, but the rise has been milder and longer, with rates increasing by about one third over two decades compared to the doubling of adolescent suicide within a single decade.

Impact

About a thousand children and adolescents (age below 18) have killed themselves each year since 2017 above the counts expected had 2007 suicide rates prevailed. Since 2008 there have been by now over 10 000 such excess deaths among minors.

If we include young adults up to the age of 24, there have been well over two thousand more suicide deaths each year lately than there used to be roughly 15 years ago.

Analyses

Back in 2019 I started a series of posts on my old Shores of Academia site (Blogspot) where I analysed the 2007-2017 doubling of adolescent suicide (The Rise).

After exploring basic statistical characteristics of youth suicide, I showed that no substantial part of The Rise is explainable by demographic shifts related to age, race, ethnicity, urban and rural areas, or geographical regions. I’ve also shown that no substantial part of The Rise is explainable by changes in suicide methods — in particular theories based on an increasing access to guns or prescription drugs do not fit The Rise data.

I’ve also shown, by analyzing trends in self-inflicted deaths ruled accidental vs. intentional, that declines in suicide stigma might explain a substantial part of The Rise among early adolescents (age 10-14) but not among teens (age 15-19).

Predictive Models

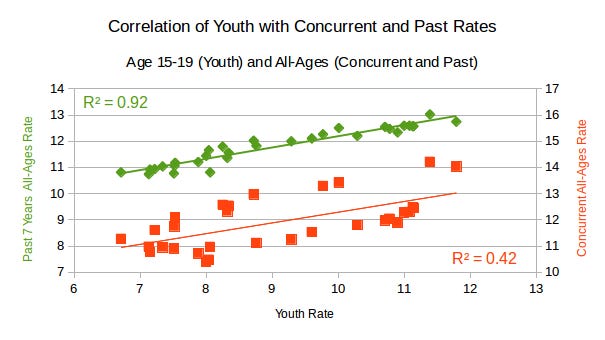

I next showed that while the correlation of teenage rates with concurrent all-age rates is not high — unsurprisingly so given that teenage and adult suicide trends diverged at times — there is a strong correlation between adolescent suicide and the average suicide rate over the past 7 or so years:

The above indicates that, in the previous decades, it is possible to predict linearly the teenage suicide rate to a high degree of accuracy from the preceding 7-year rate of overall suicide (green diamonds) — and to do so much better than if one uses concurrent suicide rates (red squares).

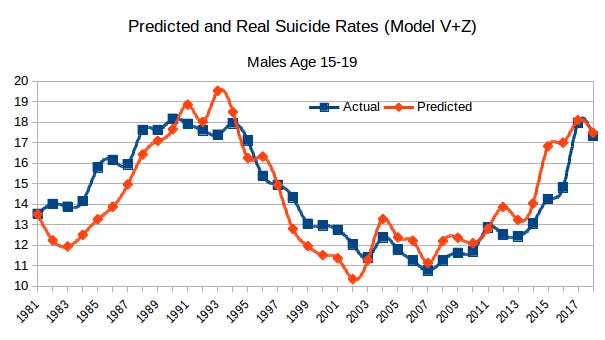

I refined this predictive model by including teenage homicide rates in order to account for differences in male and female youth trends in suicide, indicating that there is an underlying factor related to teen violence that also substantially influences suicide among boys:

Causes

Assuming the high correlation in the predictive model over the last four decades is not due to a mere chance, the question becomes which underlying factors produced the correlation.

One immediate candidate is childhood suicide trauma: the exposure to the suicide of someone important to the child. This in turn would imply that such traumas have a long-lasting impact on adolescence, substantially increasing the risk of suicide for a number of years.

A more general theory may include additional childhood trauma factors such as an overdose of a parent and similar ‘abandonment’ deaths and behaviors, as exemplified by the following graph:

So by 2019 the likelihood of having previously experienced a childhood trauma due to an 'abandonment' death of a parent or a another close adult has nearly doubled (see my March 2020 article Childhood Trauma: Adult Fatal Injuries for details).

Prevention

If suicide trauma in childhood increases suicide risks in adolescence so substantially as to have been a major factor in the doubling of youth suicide, then prevention efforts focused on teens with such a trauma might be able to considerably reduce suicide among adolescents. These efforts would have to be long-term — mere ‘grief counseling’ for a few weeks would not do. Such psychological care would also have to be accessible and affordable — ideally free for those kids whose close relative or classmate committed suicide.

New Series

I concluded the original series of analyses in early 2020 with the trauma + violence model of teen suicide. It is time to both update and extend the analyses. When I started the series in 2019, I only had CDC suicide data up to 2017; now there is 5 more years of data and together with 1970s CDC data it would allow the examination of half-a-century adolescent suicide.

There are also related topics worth exploring. One is international suicide trends, another is child maltreatment and emotional neglect, yet another is the influence of suicide news coverage in the Internet age — a theory2 that I proposed back in 2020 in connection with the especially pronounced increases in suicide among tween girls.

I also hope to examine some of the other explanations proposed over the years, such as smartphones and social media, bullying and cyberbullying, academic pressure, antidepressants, single parents, declines in religion, or parental over-protection. I might even explore more speculative factors such as junk food ingredients or microplastics and other environmental pollutants.

Finally, I seek to revise my articles with general audience in mind, so that nearly all readers can easily and fully comprehend the data analyses.

David, this is a great post. I hadn't realized that young teen girls have quadrupled. Thank you.

My apologies if my clumsy wording implied I don't respect your work. When commenting, I focus on areas of difference, but this isn't meant to insinuate that all other views are therefore valueless. I appreciate your adding the Abandonment Deaths graph, which is a compelling trend other researchers need to take seriously to move past the current mass insistence that parents' and adults' trends have nothing to do with teen depression and suicide. I will say again what I've said before: I'm looking forward to your conclusions.