The Alternate Reality of Candice Odgers (Nature's Review of The Anxious Generation)

Odgers' review of The Anxious Generation postulates a reality in which all evidence of substantial associations between digital technologies and adolescent mental health has magically disappeared.

In my previous post about the review in Nature of Jon Haidt's book The Anxious Generation, we saw that in order to publicly humiliate Haidt as an ignorant fool, Odgers created a world in which Haidt has failed to include in his book any evidence for his theory about digital technologies beyond the concurrence of their rise with the decline of mental health among adolescents.

This post is part of a series concerned with the review in Nature of Haidt’s book:

Note: the intent of this series is not to defend Haidt — he is capable of doing so on his own. The intent is to show how the debate about his new book is dominated by ideologies instead of criticism. That does not mean that there is no legitimate criticism of Haidt — I myself hope to have provided such criticism in the past and hope to provide more of it in the future.

Alternate Reality

Odgers did not stop there; she continued as follows:

Hundreds of researchers, myself included, have searched for the kind of large effects suggested by Haidt. Our efforts have produced a mix of no, small and mixed associations.

This assertion makes no sense unless not a single study found anything beyond small associations. Odgers says that none of the 'hundreds of researchers' that attempted to find a substantial association has found any.

In other words Odgers is asserting that even the correlative evidence that Haidt has amounts to at most some small associations.

If this is true, then there is no evidence of any substantial potential harms. That means the problem with Haidt is not just causality, the problem with Haidt is that he has no evidence for us to even worry about potential harms.

Furthermore, Odgers is telling us that the overall evidence overwhelmingly contradicts the notion that digital tech use is inflicting substantial harm on adolescents because at least some of the hundreds of researchers would have found at least some substantial associations.

She is essentially telling the world that we already know that the population impact of digital tech on adolescent mental health is minuscule.

That immediately implies that we should greatly reduce researching the impacts of digital tech on adolescent mental health as it will be a waste of resources when we already know — based on the work of hundreds of researchers — that any such effects are small.

Note: this would still not exclude the possibility that digital tech is inflicting damage through strong environmental impacts on the lives of all teenagers, even light users, similar to industrial pollution or second-hand smoke; such impacts though would seem a lot less plausible if there were no substantial risk elevations for heavy users.

Reality: Digital Tech and Teens

So what is the actual reality regarding associations between digital technologies and adolescent mental health?

The reality is that there is overwhelming evidence from large surveys that teens who report using digital tech heavily (5+ hours a day) also report much higher risks of mental health problems than other teens -- often double the risk of serious disorders such as clinical depression or attempted suicide.

Furthermore, the heavy users in these surveys have constituted over 20% of all teens since early in the previous decade (and much higher portions on more recent surveys).

A good starting point is Media Use Is Linked to Lower Psychological Well-Being that documents associations found in large-scale surveys of adolescents in the U.S. and UK:

Across three large surveys of adolescents in two countries (n = 221,096), light users (<1 h a day) of digital media reported substantially higher psychological well-being than heavy users (5+ hours a day). Datasets initially presented as supporting opposite conclusions produced similar effect sizes when analyzed using the same strategy. Heavy users (vs. light) of digital media were 48% to 171% more likely to be unhappy, to be low in well-being, or to have suicide risk factors such as depression, suicidal ideation, or past suicide attempts. Heavy users (vs. light) were twice as likely to report having attempted suicide. Light users (rather than non- or moderate users) were highest in well-being, and for most digital media use the largest drop in well-being occurred between moderate use and heavy use.

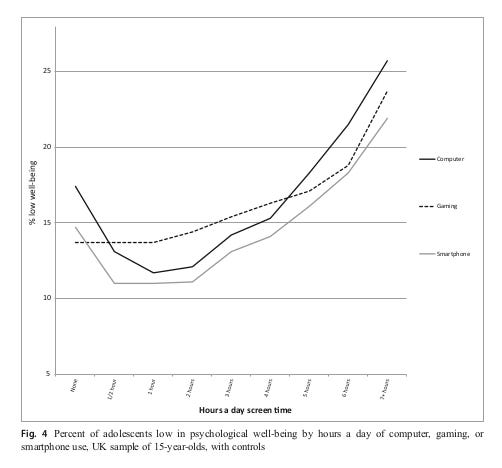

The study is full of graphs like this one:

or this one:

I've seen no evidence whatsoever that would in any way put in question the analysis above, either due to errors or bad methodology.

I've also seen no evidence whatsoever that there exist any other comparable large-scale surveys that contradict these results.

Reality: Social Media and Girls

Let us now look briefly at some evidence of associations between social media use and adolescent mental health.

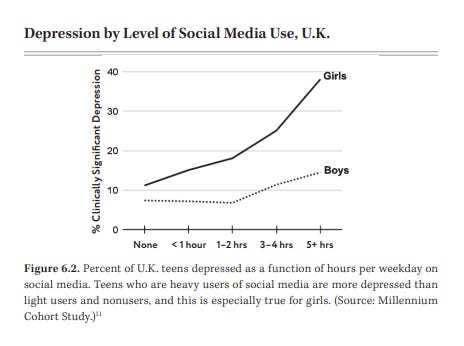

The best study I know of is titled Social Media Use and Adolescent Mental Health: Findings From the UK Millennium Cohort Study and is written by the epidemiologist Y. Kelly and three of her colleagues. The study examined data on nearly 11 thousand 14-year-old students circa 2015 and found that greater social media was associated with greater online harassment, poor sleep, low self-esteem and poor body image. Furthermore, it used results from the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire to reveal that the 25% of girls (and 12% of boys) with 5+ hours of daily social media use have 2.1 times the risk of depression than do girls (and boys) with lesser use.

Some of the results are extremely robust: the 2.1 ratio of depression risk is the result of comparing over one thousand girls in the 5h+ category with the four thousand girls in the lesser categories. This is not a result that could be attributed to a sampling error or to incorrect responses.

While for boys the rise started only at 3 hours, for girls this relationship was fairly linear:

Note: these are kids in serious risk of clinical depression per the MFQ results — the actual rates of clinical depression would be lower but should be roughly proportional.

Again, I've seen no results of any other comparable surveys that would contradict these results in any way. That is not to say that we should presume that teen girls of any age (rather than 14), at any country (rather than UK), at any particular year (rather than circa 2015), using any reasonable measures of social media use and depression risk distinct from those used in the Kelly paper, would find the same associations.

We can look, however, at a meta-analysis provided by the paper Time Spent on Social Media and Risk of Depression in Adolescents: A Dose–Response Meta-Analysis -- the only one its kind, as far as I know (other social media meta-analysis papers ignore risk elevations and instead use -- and then routinely misinterpret -- rank correlations).

The authors looked at twenty-one cross-sectional studies and five longitudinal studies (total of 55,340 adolescent participants) from around the world up to 2022 and found that more screen time was significantly associated with a higher risk of depression symptoms (OR = 1.60, 95%CI: 1.45 to 1.75) and that the association was stronger for adolescent girls (OR = 1.72, 95%CI: 1.41 to 2.09).

They also found that the risk of depression increased by 13% (OR = 1.13, 95%CI: 1.09 to 1.17, p < 0.001) for each hour increase in social media use in adolescents.

If we look at Figure 2 in the paper, we see that the Kelly results are typical for girls and somewhat low for boys:

Some readers may think that a 13% increase is not so bad. Remember, however, that this is per hour (for boys and girls combined) -- so even for teens with 4+ hours of use this translates to a massive increase of depression risk.

Note: proper models use odds ratios rather than risk ratios, but the latter are a reasonable approximation when the harm prevalence is not very high.

If you think that most teens spend less time than that on social media, look at the Gallup results from 2023:

So even after the pandemic, most teens report spending at least 4 hours a day on social media; and nearly 2/3 do so at age 17, with the overall average being nearly 6 hours a day. Furthermore, girls spend nearly an hour more on social media than boys.

That alone is no doubt alarming to the vast majority of parents, as well as teachers and pediatricians, but of course Odgers never mentions any estimates of time spent on social media nor does she entertain the possibility that its use by teens is excessive.

Combined with the results on elevated risks for heavy users, it is easy to see that if these risk increases are caused by social media use, then social media alone could explain a massive rise of depression among adolescents.

Note: the crucial question is of course causation, but a scientific debate about causation with Odgers is impossible, since she is unwilling to acknowledge that any of these risk elevations even exist.

Censorship and Magic

Some may object that we first need to look at the studies Odgers does mention before we object to her censorship of elevated risks and misrepresentation of reality.

No, we do not.

Odgers does not say that Kelly and others found substantial risk elevations but that subsequent analyses found that these were miscalculated or that, say, all such results fail to account for basic demographics like sex and age.

No, Odgers simply refuses to admit studies like those by Kelly even exist.

Nevertheless, we will look at the studies mentioned by Odgers in separate posts. What we will see is that some of the studies are misrepresented by Odgers and that the rest relies on censorship of elevated risks and on other tricks to assert lack of association.

Censorship and other tricks used as pretend magic can of course create the illusion that some inconvenient evidence has disappeared — but elevated risks like those found by Kelly and many others do not simply cease to exists just because some studies use censorship to ignore their existence.

Science and Language

Apologists for Odgers may object that terms like 'small' are entirely subjective and it's up to Odgers to decide what she deems to be small.

There are, however, two problems with this defense.

First, Odgers directly implies that correlative evidence overwhelmingly counters the possibility of substantial impacts on adolescent population, and that is a factual assertion that we have just seen to be egregiously false.

More importantly though, such a defense of Odgers admits that she and the editors of Nature have abandoned science and embraced ideology where it is permitted to use language to mislead the public as much as possible.

Indeed her use of the word ‘drastic’ in her assertion that some study (we will look at the this study in a separate post) “has found no evidence of drastic changes associated with digital-technology use” does suggest that she is using language as tool to mislead while being mindful of plausible deniability.

In science, we should never dismiss some results as 'small' or 'weak' while omitting the actual results -- especially if there is no consensus that such results are actually small or weak.

Odgers (and Nature) dismiss results that the vast majority of Nature readers would never dismiss as small -- after all who in their right mind would discount as small the doubling of suicide and depression risks affecting one quarter of all girls?

The only way Odgers can dare to dismiss such results is while simultaneously censoring the results. Without this censorship, most readers would immediately cease to trust her judgment and many would promptly ridicule her.

Omission of actual findings is a crucial tool for Odgers; Nature is signaling its approval of such censorship by publishing a review that is entirely dependent on it.

To put this into a perspective, imagine that in 1964 Nature would publish a review by Odgers of the Surgeon General report on smoking and health and Odgers would omit every actual finding of elevated risks and instead dismiss all associations as too small to warrant concerns about substantial population impacts of smoking on health.

Imagine that Odgers would declare that the association of smoking with mortality (a key result of the report) is too small to justify grave concerns over smoking -- but she would omit the finding that male smokers of similar age have a 70% elevated risk of death compared to non-smokers.

Note that in Kelly the depression risk for girls using social media is more than double that of girls not using social media.

Such a 'review' would have been met with a widespread outrage and it would have been ridiculed as being dishonest misinformation in the service of the tobacco industry.

And yet when it comes to social media corporations, it seems anything is allowed nowadays within social ‘sciences' for corporate benefit.

Conclusion

The lack of widespread outrage over the censorship and distortions of reality by Nature (via Odgers) indicates that indeed truth and facts are ceasing to matter in social sciences as the field moves away from science and toward ideologies.