If we go by title alone, Haidt’s The Teen Mental Illness Epidemic Began Around 2012 should have been primarily about the starting point of an epidemic. In reality, Haidt spends most of the article explaining that there really is an epidemic (though I’d prefer the term crisis).

That said, there is still much emphasis on the year 2012. All graphs have a bold vertical line at the year 2012 to remind the readers that Haidt thinks the epidemic started around the year 2012.

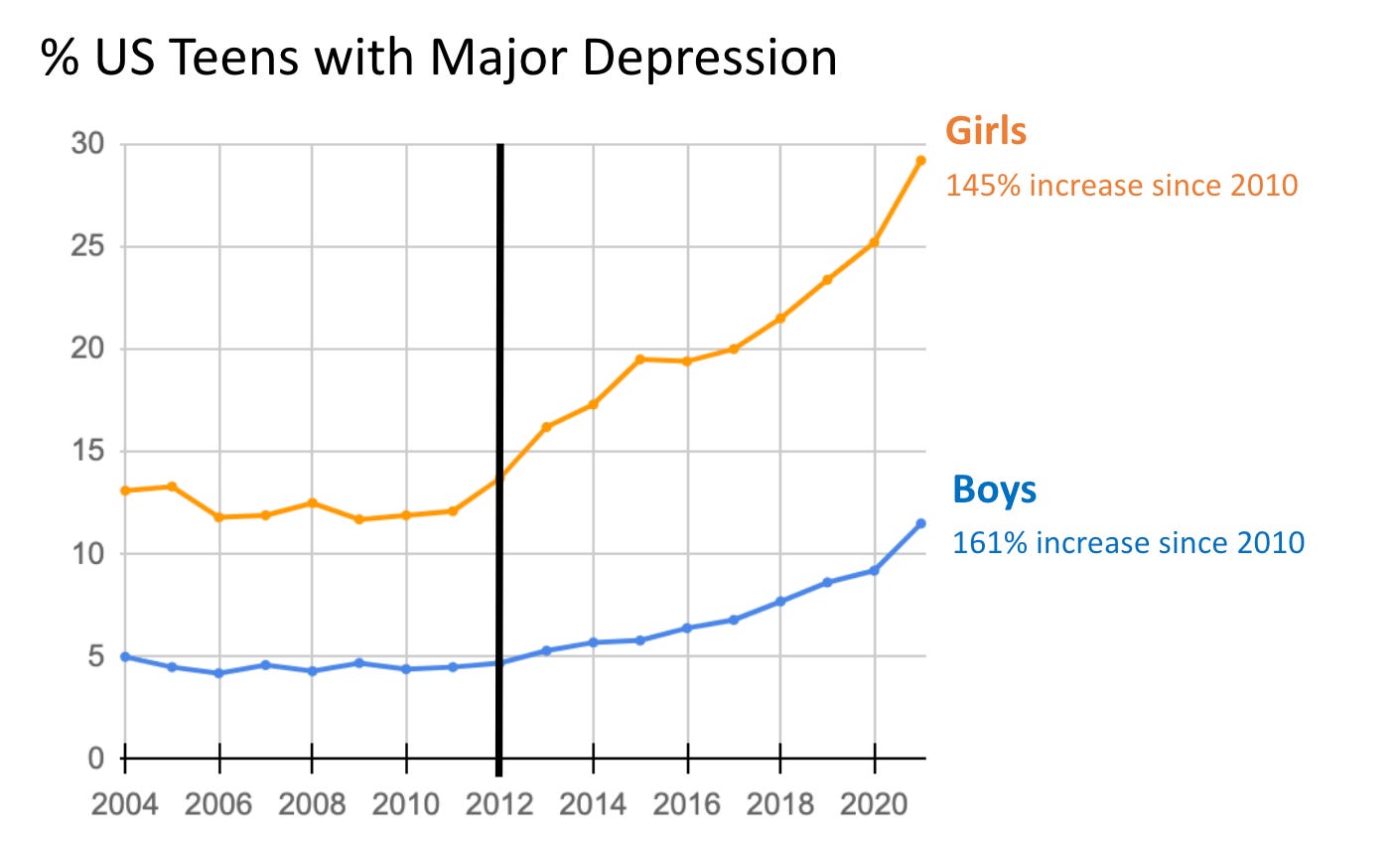

Sometimes it makes some sense, as in this graph of adolescent depression:

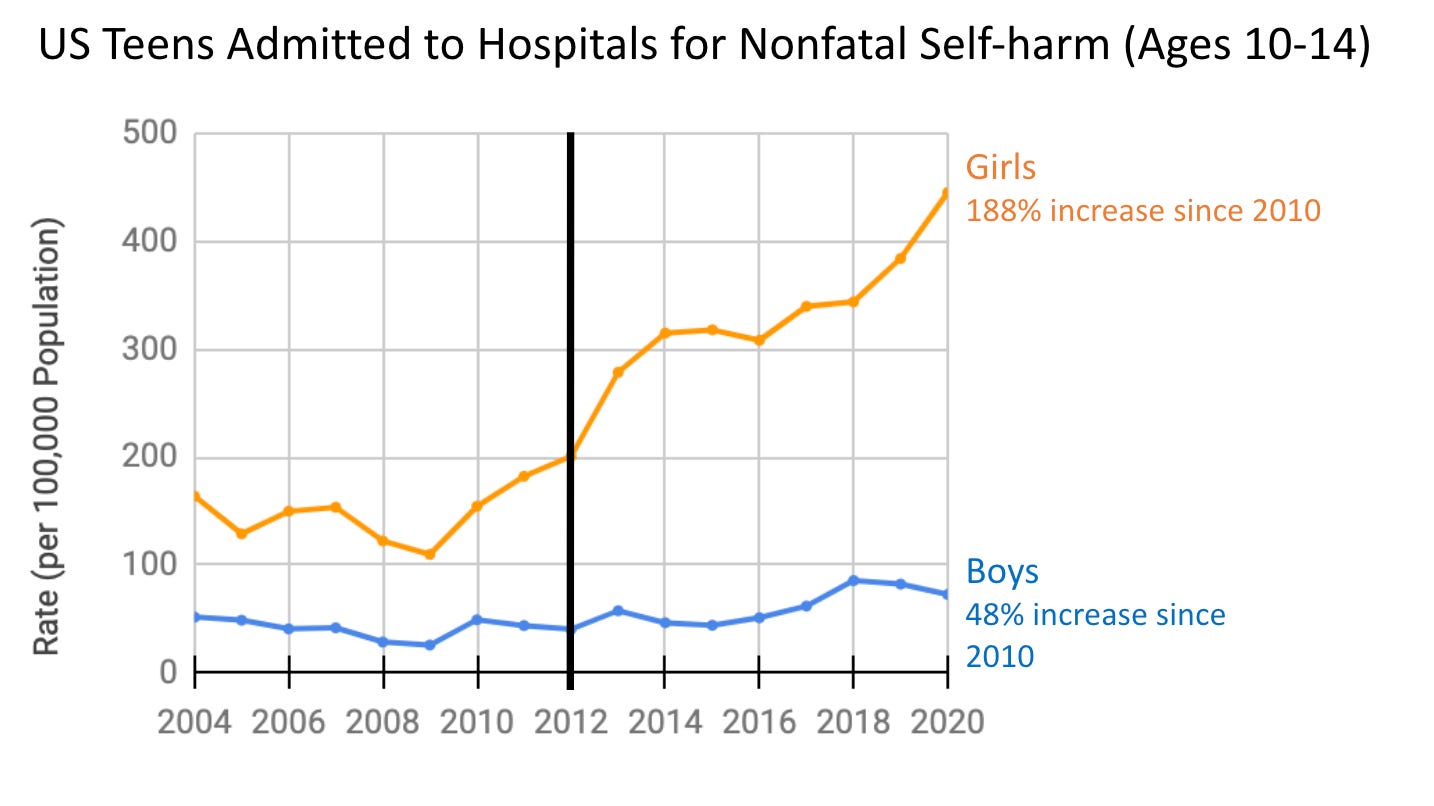

Sometimes it makes less sense, as in this graph of teen self-harm:

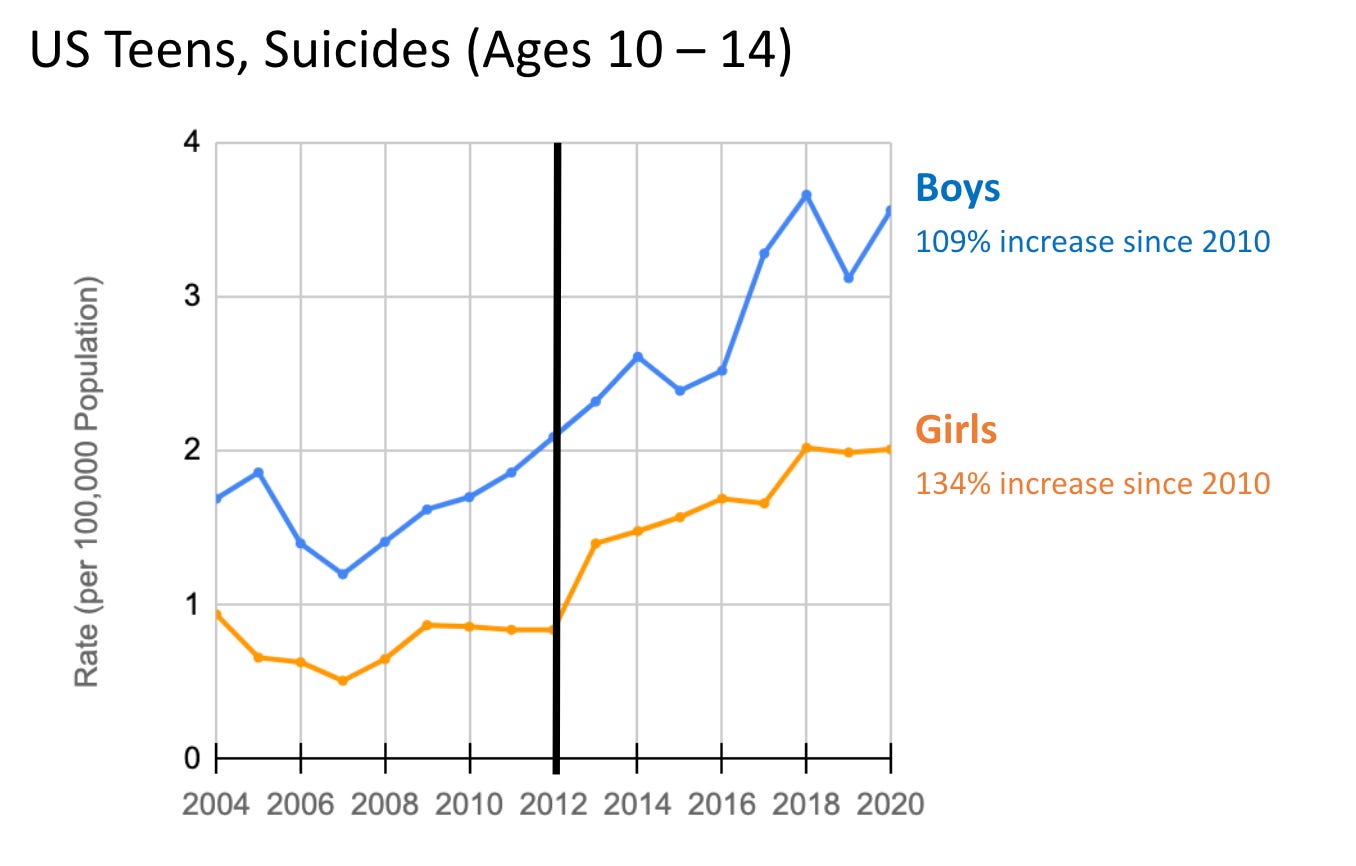

And sometimes it makes no sense, as in this graphs of teen suicide:

In fact, out of the 17 trends on various graphs given by Haidt, the year 2012 seems to be the obvious starting point of a long-term rise only for depression among girls. One trend out of seventeen.

Rises in suicide and self-harm, in particular, point to earlier starting dates, 2008 and 2010.

Haidt’s focus on 2012 is a bit odd in his commentary on the following graph:

What could have changed right around 2012 that hit tween and young teen girls hardest? (I’ll answer that in a later post.)

Right around 2012?

Clearly, the upward trend (among girls) began in 2010 and the year 2012 was unremarkable — it was 2013 that saw an acceleration of the rise.

Haidt’s emphasis on the year 2012 is even more puzzling below the following graph:

This sudden and enormous spike, in a single year, once again forces us to ask: what changed in the lives of 10-14 year old girls in 2012?

Actually, nothing needed to have changed in 2012, given that the sharp jump was in 2013.

Furthermore, tween suicides started to rise in 2008 for both boys and girls and 2012 and 2013 simply continue the trend for boys. Perhaps we should instead ask what happened in 2010-2012 that prevented suicide of tween girls from continuing to rise.

Inspiration by Jean Twenge

The emphasis on the year 2012 in Haidt’s article mirrors a similar emphasis in Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation? — the article by Jean Twenge that popularized the notion of smartphones and social media causing a mental health disaster:

Around 2012, I noticed abrupt shifts in teen behaviors and emotional states. […] What happened in 2012 to cause such dramatic shifts in behavior? […] it was exactly the moment when the proportion of Americans who owned a smartphone surpassed 50 percent.

As with Haidt, Twenge’s focus on 2012 does not withstand scrutiny: the very graphs she provides in her essay point to earlier starting points for some behavioral shifts, such as spending time with friends or driving.

Just like Haidt, Twenge uses a rhetorical crutch to impress upon the reader added exactitude where there is none. Be it ‘right around 2012’ (Haidt) or ‘exactly the moment’ (Twenge), all we have is just the year 2012 — neither ‘right’ nor ‘exactly’ (nor ‘moment’) makes the period of 12 months any more precise.

Confirmation Bias

Haidt’s exhortation of his readers to be skeptical is particularly apt in relation to his insistence on the year 2012 being the approximate origin of the mental health crisis among teens.

Readers should keep in mind that we all are subject to confirmation bias. Haidt is thinking ahead to supporting his arguments about social media and so fails to question the very notion that there is a common starting point to the mental health crisis among teens.

While minor, the misuse of language and evidence that I criticized above is a hint that Haidt’s thinking was clouded by the effort to persuade his readers — and perhaps himself — about the single time origin.

We should also be wary of persuasion that is not based on evidence — such as bold lines at 2012 in every graph. Perhaps Haidt should trust his readers more and let us each decide independently without such heavy-handed abetment.

Conclusion

Haidt failed to present convincing evidence that the mental health crisis among adolescents has a single origin in time. Furthermore, the year 2012 is the obvious starting point of a long-term rise only for the trend in depression among girls.

Notes

The epidemic terminology: readers may recall that I previously warned that the term ‘epidemic’ may mislead us into thinking of the mental health crisis in terms of a single problem (‘illness’) with a single cause (‘virus’). In reality we may be dealing with a more complex problem.

Smartphones and the year 2012: needless to say I find nothing persuasive about the notion that the proportion of Americans who owned a smartphone surpassed 50 percent in 2012 should somehow explain the sudden rise in teen depression. We are not dealing with elections not with a seesaw for kids. Also, smartphone use among adults tells us little about smartphone use among minors.

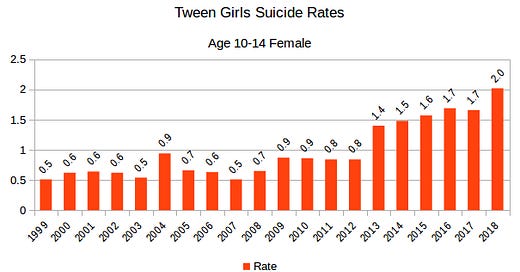

Time Trend Graphs: I think it is best to depict time trends using bar graphs so that each year is represented by a ‘segment’ of the x-axis rather than by a single point on the axis — after all each year is a 12 months long period of time. See the figure below for an example of a bar graph.

The 2013 Tween Girls Suicide Jump:

When I noted, back in 2020 (The Rise: Tween Suicide Trends), the conspicuous jump in suicide among tween girls, I wrote the following:

For tween girls, there is no severe change until 2013, when there is a fairly stunning increase that has been largely sustained since.

To understand better what happened in 2013, let us look at tween girls suicide rates:

We see there is indeed a massive jump from 2012 to 2013. Moreover, the increase has been sustained in the following 5 years. Indeed the divide between 2009-2012 and 2013-2017 is remarkable.

[…]

I double-checked the CDC data to make sure there really is such a strong divide between 2012 and 2013 for tween girls:

Although such counts may be subject to some random fluctuations, it is important to note there was nearly no volatility in the years before and after, as can be seen from the rates chart.

The fact that rates remained as high for 5 years after 2013 suggests this was neither an anomaly nor some kind of CDC data collection error.

As to explanations, I've seen no clear evidence that there was a huge jump between 2012 and 2013 in the use of social media or smart phones by tween girls -- if there is such evidence it would be worth investigating further.

As to news media suicide coverage, there was Amanda Todd (15) in October 2012, Hannah Smith (14) in August 2013, and Rebecca Sedwick (12) in September 2013 -- plus a number of other widely covered suicides of young girls supposedly linked to bullying on Ask.fm. Considerable work would be needed to estimate if there really was a huge increase of girl suicide news coverage between 2012 and 2013 -- and how it proliferated among tween girls.