Haidt: Experimental Evidence

Social media exposure or intervention experiments measuring MH disorder effects seem rather rare and lack evidence of persistent changes.

In section 5 of Social Media is a Major Cause of the Mental Illness Epidemic in Teen Girls, Haidt presents experimental evidence. The good news is that Haidt this time actually discusses several studies — the bad news is that only one is truly relevant.

Study Outcomes

Haidt notes that most experiments are done on college students or young adults because it is difficult to get parental consents for a minors — that is an understandable limitation.

What is less understandable is that Haidt fails to differentiate between studies concerned with MH disorders and those concerned with peripheral issues such as FOMO and body image.

After all, the thesis Haidt is trying to prove is that social media caused a massive increase of adolescent mental illnesses. Does Haidt expect readers to just accept FOMO and body image declines as a convincing evidence of mental illness causation?

So when Haidt reports a study count — most studies on his list found significant evidence of some effect — the reader should wonder if this majority would hold had the outcome been restricted to MH disorders.

Studies of auxiliary outcomes such as FOMO or body image may of course help elucidate why MH disorders are rising, but they should not be mistaken for evidence that MH disorders rises are caused by social media.

Haidt also does not differentiate between well-being and ill-being: a slight increase on some depression scale might actually be accompanied by a slight decrease of depressed persons (per some reasonable cut-off point on the scale). For this reason mere well-being outcomes are seldom strong evidence of ill-being, at least without further analysis.

Of the three studies Haidt cites directly, only one has a credible indicator of ill-being related to MH disorders.

Study Designs

Haidt also fails to count exposure studies and intervention studies separately — the difference so fundamental that these two categories should perhaps be treated entirely apart. The first kind compares exposure to social media with exposure to some (presumably) neutral activity, while the second kind compares a group subjected to intervention with a control group.

Of the three studies Haidt cites directly, only one has the intervention design.

Time Intervals

Haidt does pay attention to time, noting that nearly all the intervention studies failing to find effects involved a week or less, which Haidt explains by withdrawal symptoms.

This is a valid observation and a credible hypothesis, albeit unsubstantiated — are there no data allowing Haidt to differentiate short-term intervention effects by degrees of social media use?

Furthermore, Haidt needs to ask if any of the intervention studies lasted long enough to rule out mere temporary response to change. If I am not mistaken, only one study on the list lasted over 4 weeks, and that was the one intervention study that failed to find effects.

The Exposure Studies

The body image study is at best a proof of concept, since the exposure is heavily artificial: 10 manipulated selfies of ordinary women (not celebrities) in a row. It is unlikely that this exposure is anywhere close to realistic Instagram use by most girls. Furthermore, the effect was found only for girls exhibiting high Social Comparison Tendency, and no reason is given why the rather slight declines in body image shortly afterwards should be more than ephemeral.

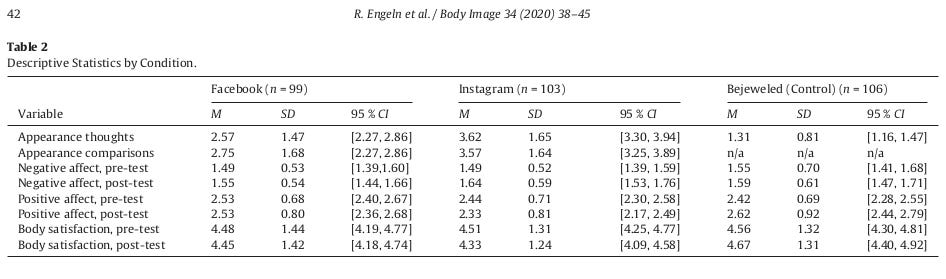

The second study included immediate effects on positive and negative affect and had a fairly realistic — albeit brief — exposure method: the three groups of college women spent seven minutes each either using Instagram, or using Facebook, or playing Bejeweled.

The Instagram group had decreased positive affect and increased negative affect; the changes, however, appeared very small. For example, the group playing Bejeweled had positive affect increase from 2.42 to 2.62 (+20), while the Instagram group had positive affect decrease from 2.44 to 2.33 (-11) — so the magnitude of the change was much smaller for Instagram than it was for playing Bejeweled!

The intervention study

The intervention study showed considerable decrease of mean BDI score for those in the intervention group whose BDI score indicated high risk of depression (BDI 14+):

It is obvious that such a decrease translates into a drastic reduction of students above the clinical cut-off (BDI 14+).

One major question is whether the declines would hold if the intervention lasted beyond four weeks. The problem is that depressed people may not be responding so much to stress levels as to changes in stress levels. If so, we could see their depression risks rise gradually if the intervention continues, because in the absence of further stress declines the depression risk returns to its natural level for each individual.

The study authors expressed regret for not measuring BDI at WK2 and WK3. Such data might have revealed useful information about depression trends during the intervention.

Discussion

Haidt still relies on readers doing most of the work: deciding which studies have results directly relevant to adolescents and mental illnesses, which studies are sound, which studies provide best evidence, and so on.

Conclusion

The one intervention study discussed by Haidt appears to be credible evidence of declines in depression, but such studies need to be replicated in various environments and for longer periods of time.

I understand the prudence of "hold on there, pardner..." with respect to Haidt's extrapolations. However, there exists a preponderance of evidence for the power of social learning theory to explain social impact on behavior. It seems to me a very small leap to imagine that social learning occurs through social media (not just semantically), and not simply through direct observation of another child punching Bobo Clown. The recent riot in New York precipitated by some off-handed comment of a social media leader seems to be a good but unfortunate natural experiment example.

Thank God some people have resistance to social influence (although some have too much resistance), hence we have a stochastic dispersion of these phenomena. But my hunch is that some of this resistance for the influence of social media on some youth is some "good enough" parenting.

I greatly appreciate your work, which makes us all think more clearly.